Founders have changed the world and will continue as long as capitalism exists. Our system motivates bright individuals to pursue dreams and build companies that improve human lives, just as trees in a canopy compete vertically for sunlight. For us investors, we need not miss out on these game-changers. We can participate in the rise of these companies alongside their founders, and if the analytical judgement is cast correctly, stand to benefit immensely from their journey.

Are all founder-led companies start ups?

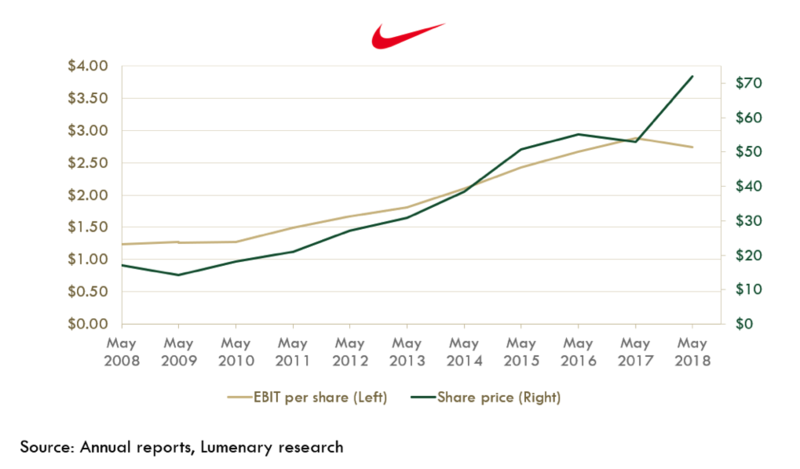

Investing in founder-led companies does not mean venture capital investing – there are over 2,000 listed founder-led companies globally, varying in age, size and industry. Not all founders work on new and shiny products, only a small proportion are start ups. In fact, there are many blue-chip founder-led companies that are not in the technology sector, and these global household giants should resonate with many of my readers: Marriott, Morningstar, Hermes, Walmart and Nike.

What are the risks of founder-led companies?

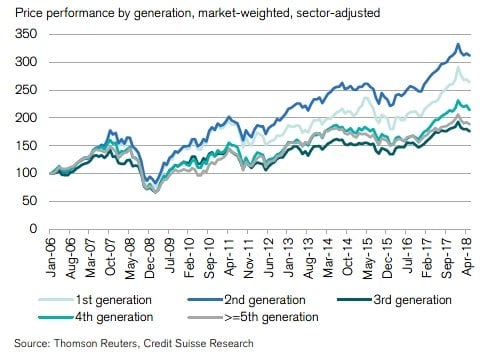

The pros of investing in founder-led companies are well documented by academics and practitioners alike – Credit Suisse and Bain have quantified a +7% outperformance since 2006. Other studies show multi-decade alpha. In business, skin in the game matters and that is why founders make great business owners and operators.

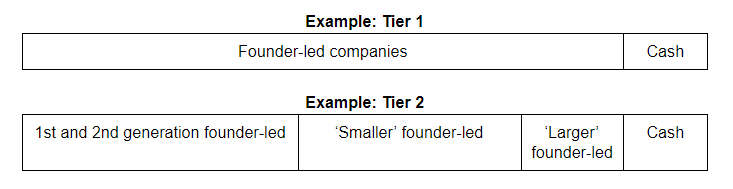

But not all founders are great. Not all founder-led companies turn out to be the next Amazon. Hence everything in moderation, and why diversification is needed to dampen the volatility of owning just one company. This is where a clear portfolio construction recipe comes in.

I have previously likened portfolios to making a cake in this previous publication here . We select our best ingredients and apply them in the right proportions before baking in an oven at the right temperature. What generates returns is not what has happened, but what will happen. And proportions are crucial.

Instead of baking one cake with all our cake mix and hoping it turns out well, we should divide the cake mix to make many cakes. With each cake we make, risk is reduced. That is the key to a well-balanced portfolio of founder-led companies. The sum of the parts is always greater than the whole, especially when it comes to risk management.

There is an optimal way to diversify and the framework for this process is tied with the concept of vintages.

How to diversify a portfolio of founder-led companies

The least volatile founder-led companies are also usually the oldest. Think Walmart, Hermes and Nike, who have each existed for decades. The advantage of these generational companies is the stability of growth and predictability of dividends. They move like ocean liners, their brands carry inertia that spins off free cash flow consistently. You can rely on these founder-led companies to deliver slow and steady growth to your portfolio. The advantages are not without risk though. Older generational companies can become complacent. Their founders may have already reaped the rewards of their lifetime of efforts and become content with sitting back and relaxing. Their succession planning may not be smooth. The companies themselves may not be built the right way to adapt to changing environments. Ocean liners have a huge turning circle; it becomes impossible to navigate fast-changing conditions when they have only been built to travel in straight lines. I’ve written previously about how up-and-coming companies can lower the risk of a portfolio here.

This is why portfolios should be built to capture the full spectrum of founders from different vintages. You want both ocean liners and speedboats. Younger founders are hungry and motivated. They are free of the shackles imposed by legacy constraints. In this day and age, issues caused by use of outdated technology can prove significant for incumbents – you can observe how difficult it is for banks to transform their systems. It is easier and faster to build from scratch than it is to modify, much like how building a new house is faster than renovating an old building. When the pace of change increases, newcomers have the advantage. Niches open up in fast changing industries, and I’ve previously outlined some of these in this article.

Take for example a company my fund is invested in. It’s a Dutch company called Adyen in the global payments market. They’ve been built with technology from the ground up that allows them to outcompete incumbents. As a result, they have been able to win significant market share in a very short period of time and capture the accelerating change in consumer payment behaviour.

When it comes to founder-led companies, there are pros and cons to both old and young. Having all your eggs in either one or the other would be unwise. Spread your portfolio across founders from all vintages.

You want to build a fleet that encompasses the ocean liners, giving stability and reliability, and mix them with speedboats who can navigate changing environments and adapt with the times. This is what can truly mitigate risk.

Skin in the game – when theory meets practice

A final question and thought for my readers: which of these investment opportunities is inherently riskier over the long term:

- Multinational blue-chip where the board has employed a salaried CEO on a 5-year contract; or

- A mid-cap company where the founder retains majority ownership, is the CEO and Chair.

The multinational blue-chip has existed for much longer, so its share price is more predictable, less volatile. The mid-cap founder-led company has a much more volatile share price – analysts have a wide variety of opinions regarding its prospects.

But which one is riskier over the long term? Which company would you rather invest in?

The answer depends on your understanding of the difference between risk and volatility. One investment is more volatile but is actually less risky over the long term.

Happy compounding.