Short-selling is a trading strategy, not a long term investment strategy. It relies on correctly identifying both the direction of the stock price movement and then anticipating market sentiment. The “difficulty to benefit” equation is not one we view favourably

Taxes and interest are hidden costs that further erode any potential short-selling profits

Profiting from market sentiment

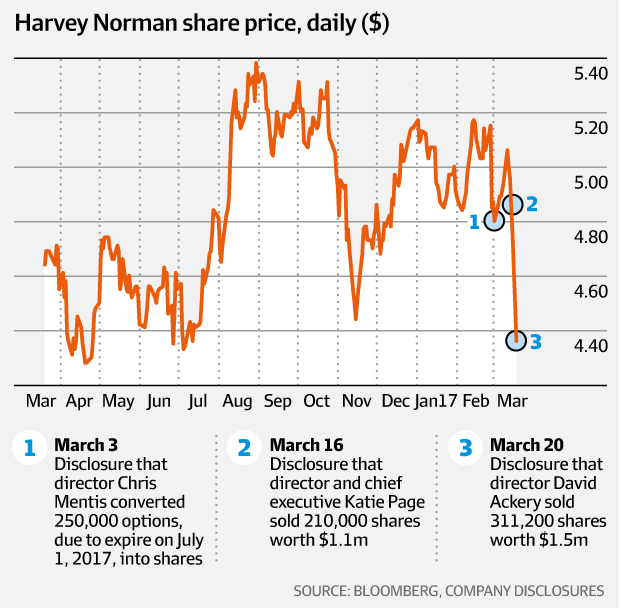

Since the start of this year, Harvey Norman (HVN) and Myer (MYR) have been on the receiving end of increased short-seller activity. The stock prices of both retailers have decreased significantly since the start of the year with the imminent arrival of Amazon(AMZN) to the Australian retail market.

Source: AFR

Whilst many have found success with short-selling strategies (think the film The Big Short), we are not proponents of this style of investing for three main reasons. First, short-selling relies on predicting market sentiment. Short-selling relies on being ahead of the market and selling before the rest of the market does. Unlike how it is portraying in The Big Short, this is difficult to do consistently over the long run, as every short sale relies on a buyer who believes in the opposite – that the stock will appreciate. With the high level of public information available today, we are sceptical of those pundits purporting to be able to consistently out-predict the market. It is for this reason we do not play the short-term trading game.

Second, not only is the level of difficulty high, but the rewards are capped since stock prices can never fall below zero. We prefer to target investments that produce profits in the multiples and short-selling does not allow that to occur. From our experience, good businesses return many multiples over the long run and gains are limitless.

Third, the short-selling strategy is very rarely based on objective information. For example, the impact that Amazon will have on Harvey Norman and Myer is based on modelling and assumptions made by analysts. The market cannot accurately quantify the exact impact to Harvey Norman or Myer’s profitability. And because the trade is based on subjective information, ie the imminent arrival of Amazon, this information is available to all and not highly reliable.

Hidden costs of short-selling

It is important to highlight the impact of taxes and interest cost to the short-selling strategy which erode any profits of short-selling. Trades that occur over a period of less than one year incur a higher tax rate. Moreover, short-selling typically involves paying an interest charge during the period which the position is held, which is the cost of waiting for the stock price to fall.

The “difficulty to benefit” equation

The degree of difficulty of short-selling is high for the reasons outlined above, yet the profits are capped. Combined with hidden transactions costs that erode the potential gains significantly, short-selling seems to us a counter-intuitive strategy. One that increases the level of investing difficulty but has a cap on increased profit potential.

For us, our profitability has come from taking advantage of market sentiment that has presented itself, not predicting market sentiment. As Warren Buffett aptly describes his approach judging the “difficulty to benefit” equation: “I like to go for cinches. I like to shoot fish in a barrel. But I do it after the water has run out.”

The outcome of how the recent short-selling activity plays out may well present us with interesting opportunities should the market overreact. That is when we will join the party.