This article was first published in Cuffelinks, 31 July 2019: https://cuffelinks.com.au/avoid-acronyms-hidden-technology-niches/

______

Imagine it’s August 2030. On a crisp winter’s morning you grab a coffee in the morning en route to the golf course for a morning hit with your mates. As you drive from the cafe to the golf course, you reflect to yourself, ‘boy, how lucky am I? This great lifestyle had a lot to do with investment decisions I made 11 years ago. They have more than tripled since 2019.’

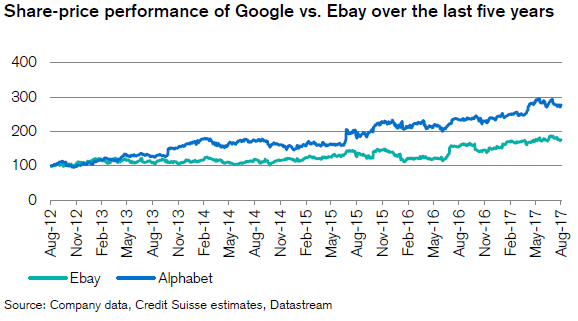

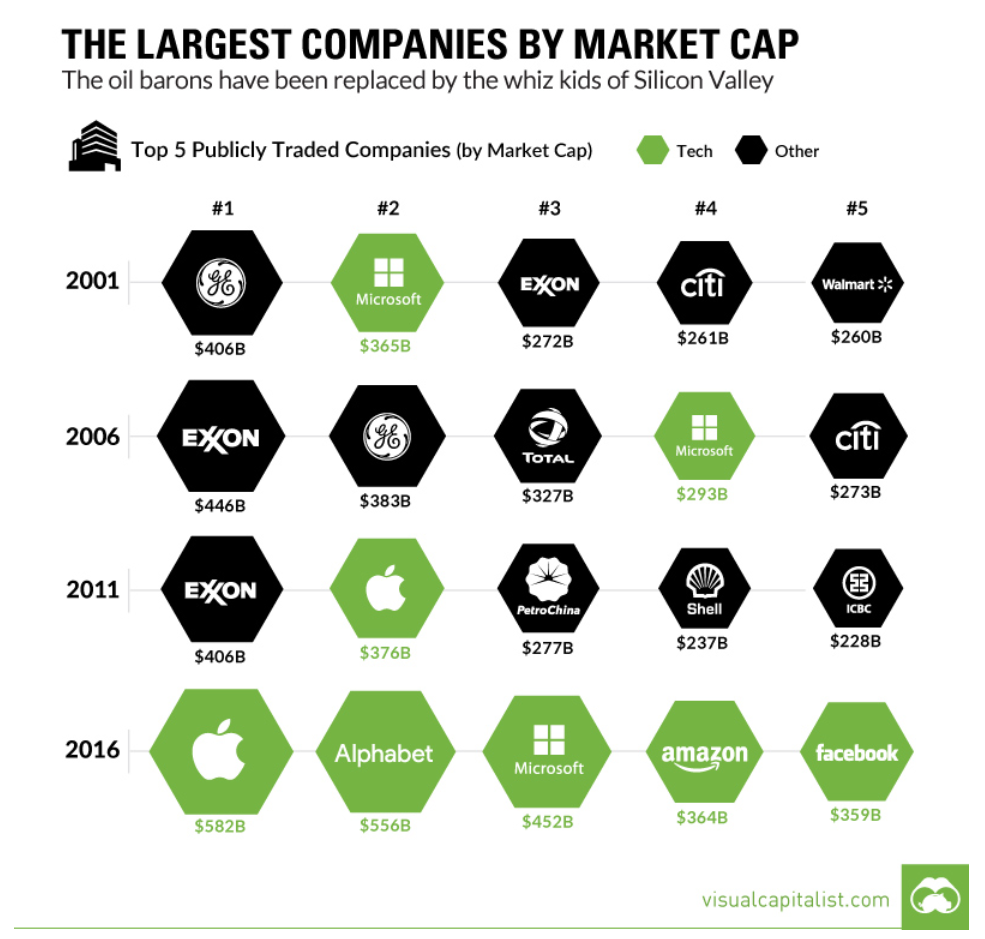

Back in 2019, the FAANGs (FAAMGs) and WAAAXs were the talk of the town. They were so hyped up that prices reached extraordinary levels. But now 11 years later, as it turns out, expectations preceded results and whilst these companies grew significantly, returns have been subdued as their growth was already priced in.

Luckily, you weren’t directly invested in these popularised companies. You were able to ride the technology boom without being exposed to the overheated stocks. In hindsight, the perfect window of opportunity to invest in other hidden gems was in 2019.

So where are the areas you need to pay attention to today, beyond the obvious? Is there a way to ride the technology boom without being caught up in overpriced stocks? I’ll share some of the areas I’m focusing on; you’ll see by the end there is indeed a common theme.

In plain sight

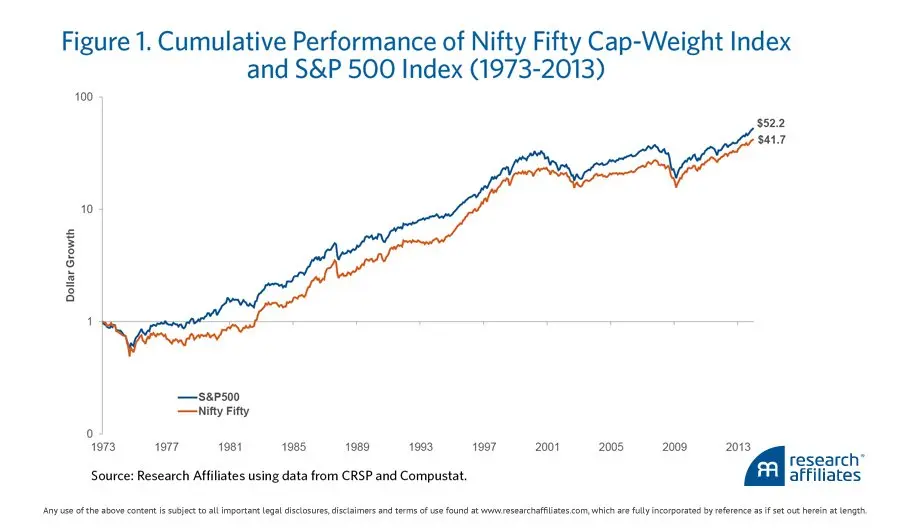

Over-popularised stocks always have monikers. They’re WAAAXs and FAANGs now, but in the 1960’s they were the Nifty Fifty. Stocks so over-referenced that commentators needed to coin a shorthand. Piling into an already overcrowded market is not where the value opportunities are.

A lot of the growth to date has been in software, but an area that is developing equally rapidly is personal devices. The next time you catch a flight or get on the train, observe how embedded technology is. How many headphones do you see?

In the US alone, the wireless headphone market is expected to grow 46% and the smartwatch market is forecast to grow 19% this year. Improvements in software have facilitated the ease of use of these devices. As buyers, we also make regular purchases so we can catch up with the advancements in battery life, wireless connection and noise cancellation technologies.

We are increasingly health-focused and that will continue to drive the development of ways we monitor our health. Smartwatches will increasingly shift from being basic trackers to more sophisticated health analysers and predictive medical tools.

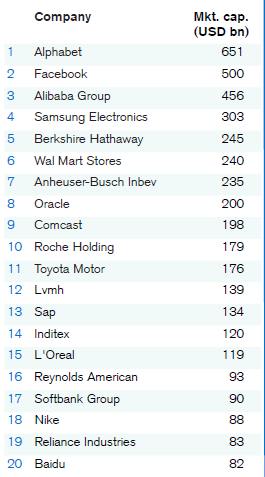

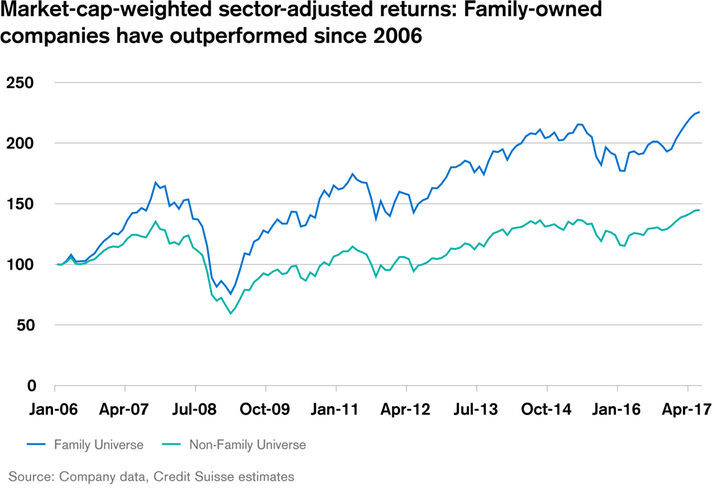

Technology is a large but competitive market. It is very difficult for any one company to fully dominate. Natural niches exist. This is where the hidden opportunities can be found. For example, Apple dominates the everyday consumer market, however is less strong in devices for outdoor activities such as aviation, marine or the automotive market. Garmin is a founder-led company that has done well in these markets.

Home is where the heart is

So far technology platforms have focused on connecting people and correspondingly building communities. Over the next decade, the focus will shift towards connecting things. And we are just seeing the start of this with our homes. The smart home market is forecast to grow at 17% this year. Demand for wireless lights, home security, voice-controlled speakers, wifi-enabled temperature controls and smart appliances will continue to increase. Households will need to phase out older technology and energy-conscious consumers will look to mitigate against rising energy prices and reduce carbon emissions.

Companies like Signify NV (formerly Philips Lighting) have taken this one step further. Where else can you apply the same technology used in our homes on a larger scale? Answer? Cities. By installing connected light systems for Shanghai, the city can showcase interactive light displays and realise significant energy savings.

Traditional ‘boring’ manufacturing and engineering companies are often overlooked but yet remain integral and major contributors to technological growth.

Hidden oligopolies

Don’t let the headlines deceive you. Many advanced manufacturers represent great buying opportunities right now; with the trade war and Brexit causing market apprehension, their stock prices have fallen. There are many manufacturers that remain integral suppliers to the technology industry despite what you may read in the headlines. Microchips and glassware are the obvious over-mentioned examples, with Foxconn and Corning being the key suppliers for Apple. But even these companies no longer represent a hidden opportunity. We need to delve deeper.

Many ‘unsexy’ and often overlooked manufacturing companies are trusted suppliers of niche components to the world’s leading technology brands. Historically, global slowdowns have only been temporary. Quality manufacturers have always been able to refill their order book once the slowdown dissipates. The best time to invest in these oligopolies is during periods of uncertainty.

Deeper research can uncover less obvious, more lucrative gems. The hidden opportunities that have stood out to us have been very specialist manufacturers that make product-critical components with very few competitors. These companies control an oligopolistic market because they have scale and switching costs are too high for their customers. For example, companies like Omron, Cognex and Keyence Corporation sell niche sensors, lasers and measurement equipment that feed into the technology sector, benefiting from the growth whilst avoiding the limelight and intense competition.

What does wireless technology rely on?

More and more we are shifting towards a wireless world. All technology services rely on wireless infrastructure and this is an area many have overlooked that I am focusing on. It’s a surprising fact that many countries are still rolling out 4G including the US and India. Moreover, the rollout of 5G networks is only just beginning this year.

We have recently invested in a Swedish cable manufacturer (founder-led, of course) that supplies customised cables essential to the development of telecommunications infrastructure. The continual improvement in technology to improve wireless internet speeds has driven record-breaking demand from its customers.

Importantly, infrastructure requires constant renewal and demand for specialist cables will always follow.

Closing remarks

What will drive your returns to 2030? No doubt technology will play a large part, but history has always shown over-popularised stocks rarely make great investments. It’s usually the ‘hidden’ or non-obvious that represent the greatest opportunities. By the time companies have made it into an acronym, it’s too late.

There’s a common theme for the next frontier of technological growth – the rising importance of not only software, but the hardware and ancillary pieces that will accompany this growth. We still live in a physical world and the hard infrastructure remains an increasingly important medium through which we can interact with technology.

Start your search in the areas above and you’ll be well placed to ride the tech boom without the inherent risks of overcrowding.

Happy compounding.

About us

Specialists in uncovering the best founder-led companies in the world. We invest in unique, overlooked companies in markets and industries beyond most managers’ reach. Our portfolio is made up of stocks that sit outside typical index constituents.

Lawrence Lam

Managing Director & Founder