This article was first published in Money Management, 15 August 2019: https://www.moneymanagement.com.au/features/expert-analysis/when-turnarounds-work

______

Investing in corporate turnarounds is like buying a broken vintage car. Most will end up in decline, but a special few will be fixed and reward their owners handsomely. When corporate turnarounds work, they yield spectacular returns in the multiples. This is the model private equity firms employ. So can ordinary investors apply the same principles to profit from these special situations? What factors should be considered in the analysis?

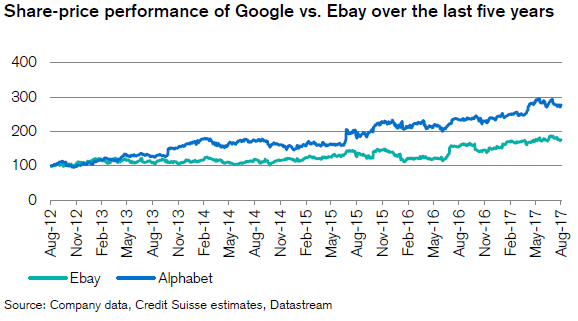

Many investors shy away from turnarounds. After all, the company in consideration is usually experiencing historical decline. Think about Qantas ten years ago. From 2008 to 2010, Qantas revenues fell by $2 billion (13% decrease over the 2 years). Add to that an industrial dispute that lasted 2 years, Qantas was a very unpopular blue chip. It’s share price fell by 82% from 2007 to 2012. But we all know what has happened since then. It turned out to be the perfect window of opportunity to invest as Qantas has returned a multiple of 4x total shareholder return since then.

Corporate decline or multi bagger turnaround?

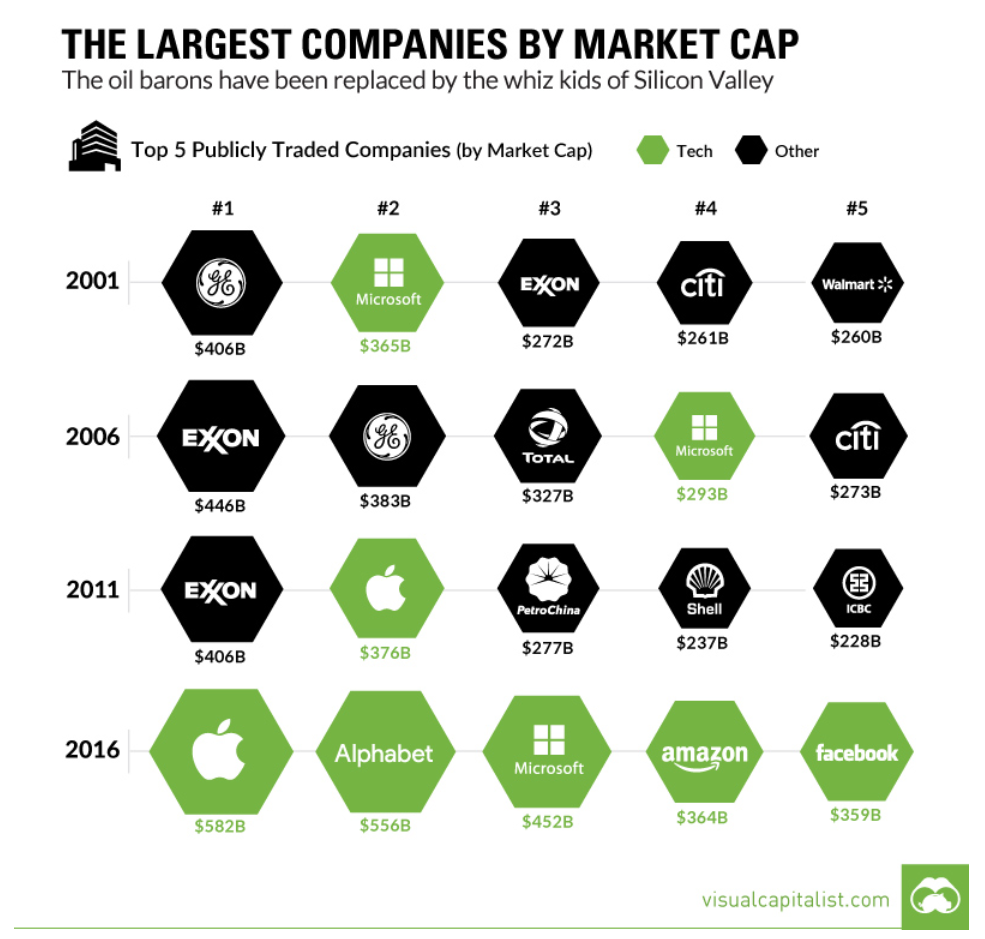

Most corporate turnarounds will not work. These companies have left it too late to adapt to changing business environment. For example, many retail companies reliant purely on foot traffic have realised too late they should have invested heavily in online sales (think J.C. Penney).

But environmental challenges exist all the time. This is not the cause of failure. It is the inability to adapt and evolve that leads to erosion of a business model. For every J.C. Penney, there are companies like Home Depot that have continued to grow with the market.

As investors, we focus a lot on asking ourselves, “are we being too optimistic? Is this a bubble?” but we should equally consider the flipside, “are we being too pessimistic? Is the stock underpriced?” Opportunities reveal themselves only to those that investigate further.

This was why Warren Buffett invested a quarter of his assets in American Express when its share price halved in 1964. The company had been left with an immense financial obligation after being defrauded by one of its clients. The trust in the brand had been severely damaged and the company was in trouble. Despite this, the clue to the future growth of Amex was in the Oracle’s analysis. After delving deeper, Buffett concluded the fundamentals of the company were robust. Customers continued to use Amex cards and the brand was unlikely to be permanently impaired. The rest is history.

Just because a company’s share price is declining, shouldn’t mean it’s an automatic write off. The very essence of investing urges us to seek out the truth through analysis.

But most struggling companies aren’t like American Express. Many have weak underlying fundamentals. Everyday investors don’t have the ability to aggressively restructure companies like private equity firms. Does this exclude investors from participating in potentially lucrative turnarounds? What are the clues investors can use to determine if these companies will be future multi baggers?

Against the conventional wisdom of corporate boards

Clue 1:

Look for companies with a smaller-sized board with less external directors. Corporate turnarounds require rolling up of sleeves. The board’s role in getting their hands dirty has greater value than being a typical challenger/debater when crucial decisions are required. Executive directors are likely to add greater value in this respect than non-executive directors.

Conventional wisdom dictates that corporate boards should separate the role of CEO and Chair. External independent directors should be favoured. Textbooks say this governance model is how corporations maintain proper checks and balances.

This doesn’t work for turnaround situations. A core ingredient in any turnaround is the minimisation of bureaucracy. The company needs all hands on deck and all hands need to be fully aligned. Often hard decisions need to be made, and made with conviction. This is not the time for board politics; independent directors looking for their next board gig won’t help the situation. Conventional governance doesn’t work in this case because there are too many chefs in the kitchen.

Surprising research

Clue 2:

Companies that implement ways to grow themselves out of decline are more likely to be multi bagger turnarounds, as opposed to those that reactively cost-cut when times get tough.

Fixing a broken vintage car isn’t easy. It requires correct diagnosis of the issues and then applying the right actions. Most of the time CEOs aren’t focused on the correct areas. Research has shown that turnaround strategies focused on building and growing are significantly more effective than those on cost-cutting[1]. It requires greater courage to launch new products or increase research and development spend in the face of decline. Most CEOs are reluctant to take career risk with this approach when conventional cost-cutting exercises like downsizing can yield immediate short-term improvements.

The right person to lead the turnaround

Clue 3:

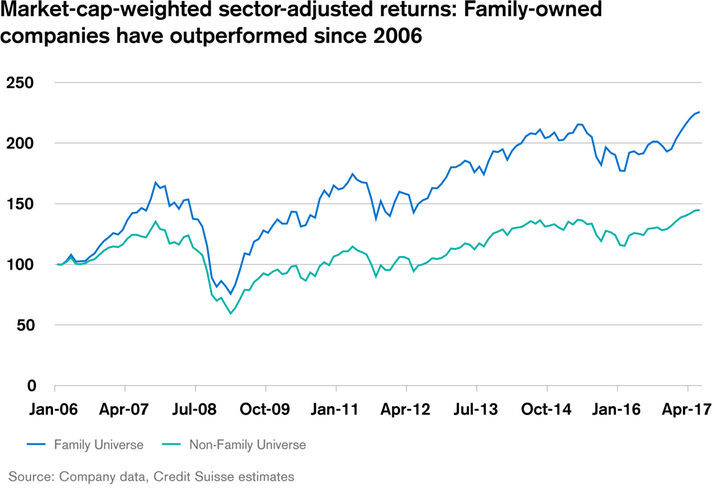

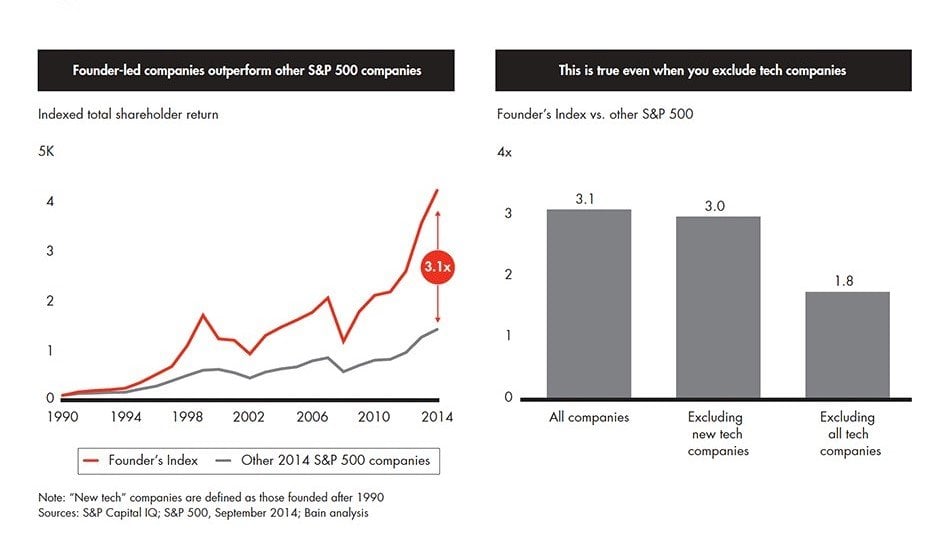

Founders are more likely to lead a successful turnaround of their companies.

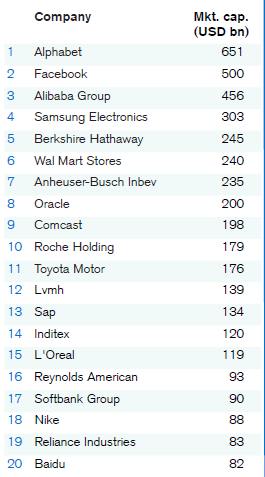

Crucial to any successful turnaround is a CEO who is resourceful, creative and an adept capital allocator. There’s a certain type that fit this mold well, those founders our fund is very familiar with.

The benefits of investing in founder-led companies are well-known. This is our fund’s specialty. It also happens to be underestimated by many investors. Founders who remain long-term managers and owners of their companies are the best candidates to lead a successful turnaround. Captains of their own leaking boat are highly motivated to repair it permanently rather than jump ship. The Corporate Governance International Review found there to be historically a 24% greater likelihood of success when founders led a corporate turnaround[2].

There are many examples of these types of leaders, the well-known ones are of course Steve Jobs and Howard Schultz. The resurrection of Apple and Starbucks can only be attributed to the brilliant impact of these founders and the heart they had in their business.

A little-known Belgian with the midas touch

Clue 4:

Look for close alignment between board, management and ownership. This is often represented by economic interest or voting rights. Being joined at the hip pocket is a wonderful thing. Strong leaders who stand to gain as much as owners is a strong clue for the likely success of a turnaround.

One media-shy businessman has had an incredible track record of rebuilding companies. Luc Tack hails from a small country town in Belgium called Deinze. I confess that our admiration for Luc’s abilities is biased. Our fund is invested alongside him and we stand to benefit from his nous.

The son of an operator of a small flax factory, it was 1979 when young Luc saw an opportunity in the growing Belgian furniture market. But it wasn’t selling furniture itself, that was far too competitive for Luc. The real opportunity was in supplying the wood instead. So the 21-year old flew to the United States, secured a wood supplier and founded a company called Oostrowood.

As he later recalls, his long-term business mindset came from his mother who always said to him, “do not cackle, lay eggs”, and laying eggs he did.

By the nineties, Oostrowood had transformed itself into a wooden flooring company and Luc began moving into an equally unsexy industry – textiles. Weaving mill companies Ter Molst and Oostrotex were eggs laid in the nineties that would later prove crucial to Luc’s future success.

On the back of the success of his diverse businesses, in the early 2000s Luc took majority control of a struggling weaving loom manufacturer called Picanol. It was 2009 and the quiet entrepreneur pumped 15 million euro into the then-ailing company that was on the verge of bankruptcy. No one else believed in the company at the time. It was a neglected manufacturing business riddled with internal division and hadn’t adapted to the changing market.

His first objective as CEO was to turn a profit. He announced that for as long as the company made losses, he would not pay himself a salary. He suffered for only one year. Since his tenure, the company has increased its revenues by 2.5x and almost tripled its net profit.

To this day, Luc Tack sets himself a measly salary of 100,000 euro each year. His focus remains firmly on laying eggs.

In closing

Investors can make a lot of money from corporate turnarounds and have lower risk as prices are depressed. The clues above help you to see whether a company has the heart, stomach and brains necessary to change their fortunes. Sometimes things aren’t as dire as we think.

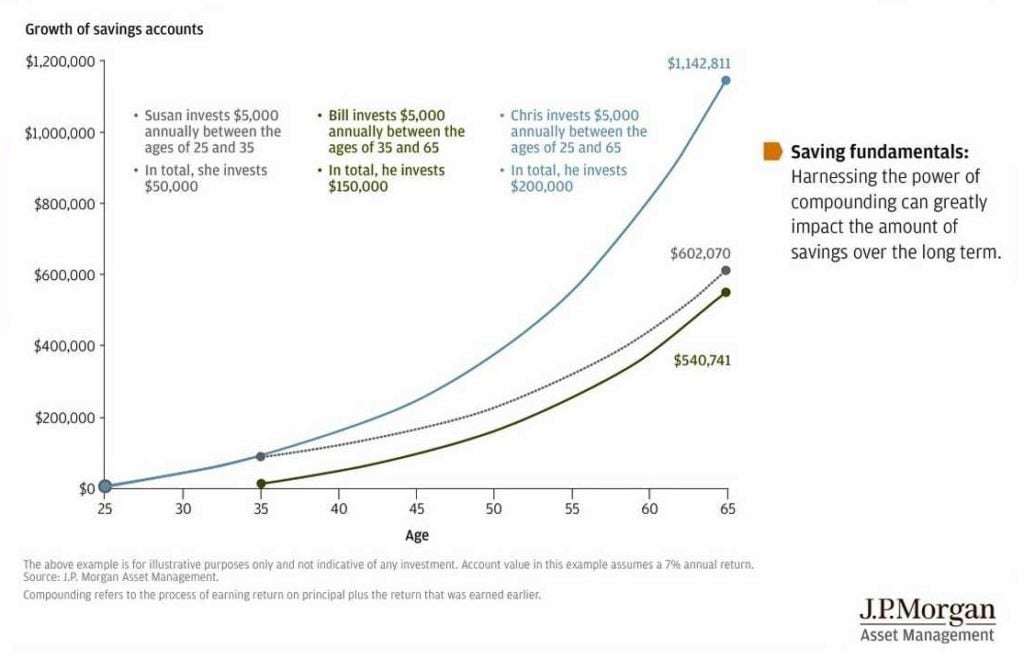

Happy compounding.

About me

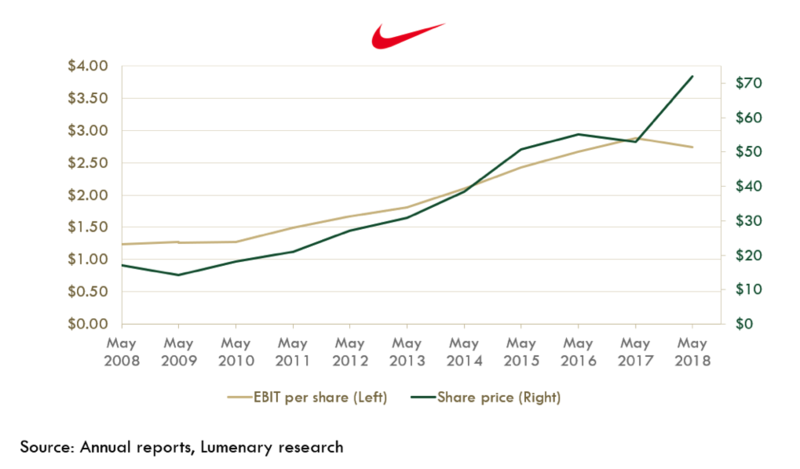

Lawrence Lam is the Managing Director & Founder of Lumenary, a fund that uncovers the best founder-led companies in the world. We invest in unique, overlooked companies in markets and industries beyond most managers’ reach. We are a different type of global fund – for more articles and information about us, visit www.lumenaryinvest.com

[1] Abebe MA, Tangpong C. Founder‐CEOs and corporate turnaround among declining firms. Corp Govern Int Rev. 2018;26:45–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12216

[2] Abebe MA, Tangpong C. Founder‐CEOs and corporate turnaround among declining firms. Corp Govern Int Rev. 2018;26:45–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12216

Lawrence Lam

Managing Director & Founder