Published in Money Management magazine 14 September 2017 issue.

Lawrence Lam looks at why compounding should not be overlooked for investors with a long investment horizon during a low growth environment.

Since 2013 we’ve been told by financial forecasters to expect a new world of low earnings growth. We’ve been told that the economic challenges in the US and Europe combined with deceleration in China has led to a new shift in economic paradigm – the “low growth environment”. Investors should temper their return expectations and respond by focusing on high-income assets such as bonds, infrastructure investments and high-dividend paying stocks. In short, capital growth will be hard to achieve, so the advice has been to focus on seeking yield/income generation instead.

For investors with a long investment horizon, I offer an alternative view. I highlight why investing purely for yield overlooks one of the most powerful and not-so-secret concepts in finance – compounding. In this article I’ll highlight why focusing on compounding can lead to superior long term returns.

Compounding – the eighth wonder of the world

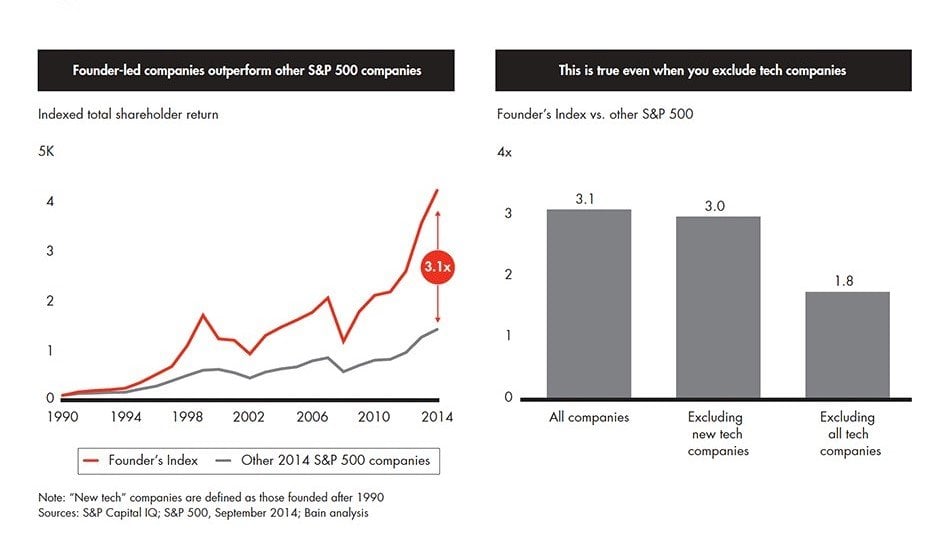

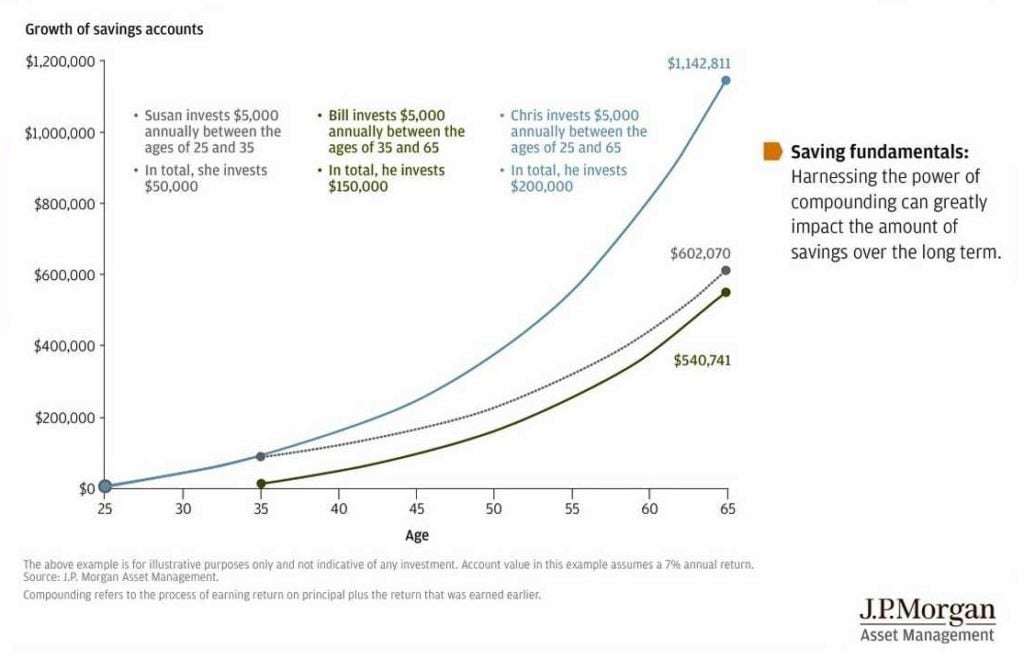

Einstein once said “compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it…he who doesn’t, pays it.” A few centuries earlier, Benjamin Franklin wrote “Money is of a prolific generating nature. Money can beget money and its offspring can beget more.” The advice given by Mr Einstein and Mr Franklin holds true even in today’s uncertain economic environment. In essence, the value of a dollar invested does not grow in a straight line. It grows exponentially. So an investor can truly harness the power of compounding by remaining invested for as long as possible, allowing returns to hockey stick in investments that have the highest return. The below chart from JP Morgan Asset Management visually illustrates the power of compounding.

Firstly, the chart shows that by consistently reinvesting, the value of an investment grows exponentially. The more money you have working for you, the more offspring it will beget you. The weakness of focusing solely on yield is that one ignores the value of reinvestment and instead values withdrawing cash from the investment. In the process of blindly searching for yield, one overlooks one of the greatest advantages an investor has. For an equities manager, instead of focusing on stocks that pay out a large portion of their earnings as dividends, the power of compounding can work in your favour if you select stocks with high rates of capital reinvestment.

For these stocks, cash is retained in the company rather than paid out in dividends. Provided the cash is used sensibly in value-adding reinvestments, it continues to compound at a much higher rate within the company rather than being paid back to investors as cash. So why choose to receive cash now when keeping the money invested generates a higher return?

Total shareholder returns: dividends or capital growth?

Unless you are a retiree or have a strong preference to receive cash, a sensible investor would choose to keep their investment compounding at high rates rather than be paid out. This holds true especially in today’s low interest rate environment. Dividends paid out as cash earn low single digit returns, whereas keeping the money on the compounding train yields the return on equity being generated – most likely higher than current interest rates if the stock has been carefully selected. So although the investor receives less cash now, the money is reinvested back into the company to develop new products, innovate, expand the business, and ultimately increase the intrinsic value of the stock.

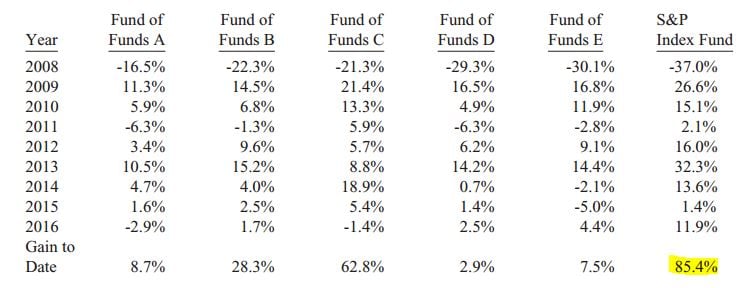

So if an investor has a long term horizon and does not have a strong need for cash, they would choose to invest in great compounders where high rates of reinvestment lead to intrinsic value growth, as opposed to cash cow stocks that pay high yield and therefore unable to compound significantly. Total shareholder returns should be the focus, not just yield.

Compounding is even more important in times of uncertainty

The focus on yield comes from the rhetoric that we are in a time of unprecedented uncertainty in global politics, markets and economics. Established companies with long histories are subject to disruption and it has become increasingly difficult for companies to grow earnings. If we take a longer term perspective we can see that this simply isn’t true. For long term investors it would be dangerous to act on these short term economic forecasts.

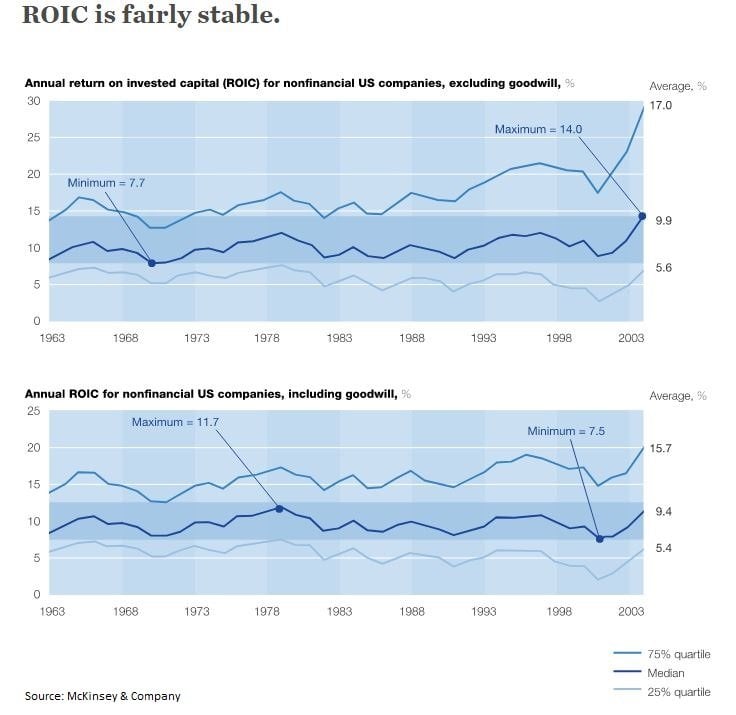

The chart below shows McKinsey’s study of the average historical rate of return on invested capital (ROIC) from 1963 to 2004 of 7,000 publicly listed non-financial US companies.

ROIC is an indicator of how effective companies are at generating returns on their capital reinvestments. For investors in companies, it is a proxy for the rate of compounding they can expect if a company was to retain its earnings rather than pay them out as dividends. Since 1963, we have had numerous wars, oil shocks, the introduction of the internet and multiple economic cycles over this long term period, the fact is that average ROIC has remained stable. Companies retaining cash to reinvest in their business have generated a return of 7% to 10% regardless of the macroeconomic environment.

History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme. And the weight of history tells us that companies will continue to compound at much the same rate. Especially in these times of technological change, it is important for companies to reinvest to adapt to new competitors to drive future growth. Now is the time to invest in companies focused on growth and reinvestment, not cash cows that return high yields.

Harnessing the power of the compounders

The ‘low growth’ rhetoric isn’t a mindset we ascribe to. On the contrary we remain optimistic about the long term prospects of quality companies. We take a long term investment strategy, we aren’t desperate for cash and would much prefer to maximise total returns rather than simply focusing on yield and miss the benefit of compounding.

The challenge for most investors is not to seek the shelter of yield in times of uncertainty, but it is to find those investments that will continue to compound over the long term.

The historical ROIC from the chart above is an average of US companies. Knowing that history is in our favour is one thing, but fully capturing the benefits of compounding still depends on being able to select specific companies to invest in.

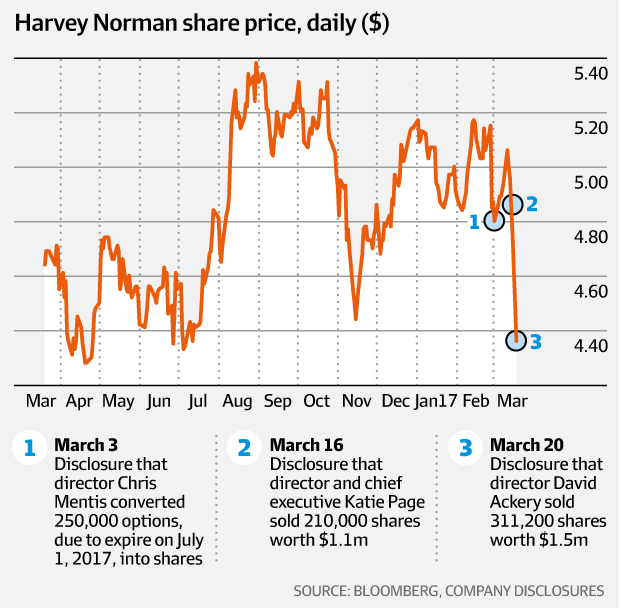

There are many ways to do this and I’ve highlighted only one way in this article via the ROIC. Another way to identify quality compounding investments is to align with quality management. A company’s ability to compound depends on its management’s ability to recognise new markets and execute growth strategies for the long term benefit of the company.

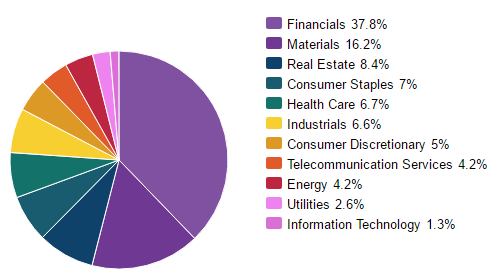

It also depends on the opportunity set available to each company and for this reason it is worthwhile for most investors to consider looking at the entire universe of companies on a global scale. The chances of finding great compounding opportunities is much improved by looking beyond local borders.

For those investors currently focusing solely on yield, you might be unnecessarily narrowing your investment options and missing out on some great compounding companies. They may not be great yield investments, but you’ll have the exponential force of compounding working in your favour instead.

Lawrence Lam is Founder & Portfolio Manager of Lumenary Investment Management, a global equities investment firm focused on investing in international founder-led companies.

www.lumenaryinvest.com